I don't know exactly when, but at some point when I was much younger, maybe nine or 10 years old, my dad had sent for and received an information package about some sort of kit car. As I recall, he was quite enthusiastic about it. It was a new concept for me at the time, this building your own car from a kit, and rather intriguing. That memory stay with me, lying dormant for many years until one day I was struck with the urge to build my own car. I'm not sure why I wanted to build a car, second childhood, perhaps. Like many of my ideas, I had no idea what I was getting into.

I've owned a lot of cars over the years, some good, some not so good. One of my favorites, and the one that I hung onto the longest was a 1966 Volkswagen Station Wagon, a.k.a. Squareback or Type III. I first saw it when I was asked by an employer to move the car out of a parking lot so that the lot could have the accumulated snow and ice removed down to solid ground. When I walked up to the car, it was barely visible, having spent the first part of the winter parked in that spot while the owner was at his home in Texas. He only owned the car so that he could have it available to him when he visited his condominium there in Steamboat Springs, Colorado where he occasionally came to ski or enjoy the mountain scenery. The rest of the year the car just sat there and the condominium was available for rent to tourists.

The first thing I had to do was uncover the car, including digging out the snow alongside the driver's side door so that I could get it open. Have done that, I crawled inside, found the ignition switch, inserted the key and gave it a turn. To my surprise, when I turned the key, the started growled and the engine cranked. That in itself was impressive, given that the temperature was well below freezing and had been for several weeks, along with the fact that the car had not been started or driven for months. The engine didn't start right up, but it did turn, so I pumped the accelerator pedal a few times and tried again. After a few more tries, the engine caught and began to run. It made a horrible sound, as if the whole thing was grinding itself to pieces, but, amazingly, it kept running. I let it run, hoping the horrible sounds would stop once the engine warmed up. Eventually they did, after a few minutes, and so I was ready to try to back the thing out of the hole where it sat. I grabbed the gearshift lever, pushed in the clutch pedal and put the transmission in reverse gear. When I was digging the show out from around the car, I had noticed that the rear tires where rather worn, with almost no tread left on them, so I had little hope that the car would actually be able to move itself over the ice and snow. I was so very wrong. As I gently engaged the clutch, the little car crawled right out of the hole. I moved it to clear spot in the parking lot, shut if off and returned the keys to my employer's office. I was impressed with this little car and I decided that if it ever came up for sale, I would put in a bid for it.

Later that year, the owner of the car decided to sell his condo. When I found out about the pending sale, I asked my boss if he was going to sell the car as well. The answer was, "Yes." I offered him $400 for the little white car and he accepted. I now owned my first Volkswagen.

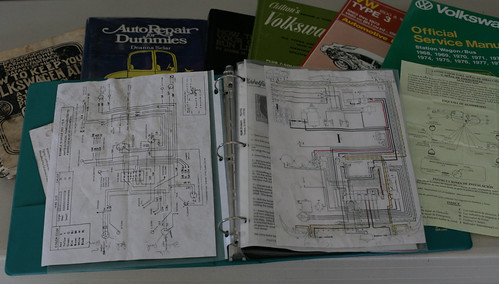

One of the things I always do when I purchase a car is to acquire a shop manual for it so that I can do some of the minor work, such as tune-ups and oil changes, myself. I discovered that there was a unique manual available for Volkswagens called

How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive, A Manual of Step-by-step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot by John Muir. I bought one. I still have it. I still refer to it occasionally. I learned a lot about Volkswagens from that manual, and a lot about auto mechanics in general. It's a great book, well written, easy to understand and follow, and a valuable resource for someone like me. That book helped me keep that car alive until just a few years ago when I passed it along to someone else, sans engine. After over 30 years, I still own parts of that engine.

When the urge to build my own car welled up within me, it was natural to think of using Volkswagen parts to build it. VW parts are modestly priced, readily available, and well suited for incorporation into a kit car project. So, I decided to build a Dune Buggy. I knew that, at some time in the past, there had been kits available for such a project, all I had to do was find one.